In addition to historically low interest rates, the US Federal Reserve has committed to an open-ended quantitative easing (QE) programme — buying mostly Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities but also, for the first time, corporate bonds of all grades from both the primary and secondary markets as well as through exchange-traded funds, among others.

Few would argue that QE, the key monetary tool for major central banks during the GFC, has been effective in averting a more severe crisis, though its longer-term success is still hotly debated.

Certainly, what started out as an emergency measure appears to have morphed into a permanent fixture. Even before the outbreak, the balance sheets for the European Central Bank (ECB) and Bank of Japan (BOJ) were still trending up more than a decade after the GFC, with only the Fed taking baby steps to normalise. The latter’s balance sheet declined to US$3.8 trillion in September 2019 from the peak of US$4.5 trillion in early 2015.

The Fed’s balance sheet has now ballooned to over US$7 trillion, equivalent to some 34.5% of gross domestic product (GDP) and well beyond levels following the GFC. Total assets of ECB and BOJ too have surged to fresh record highs, at US$7.6 trillion and US$6.4 trillion respectively — or about 53.1% and 125.7% of their nominal GDPs (see Chart 1).

See also: Markets rise when merit is recognised

Despite inconclusive evidence on its longer-term effectiveness — central banks can inject liquidity but cannot force financial institutions to lend or businesses to borrow for productive expansions — emerging markets (EMs) from Poland and Croatia, to Hungary, Turkey, South Africa, India, Indonesia and the Philippines have also begun to include QE in their crisis-fighting arsenal. On the home front, Bank Negara Malaysia’s holdings of Malaysian government papers spiked sharply higher in April and are up RM8.5 billion year to date.

Clearly, what was once unthinkable and unprecedented is now rapidly turning into the norm — with no end in sight. Some market observers have taken to calling these central banks’ asset buying “QE infinity”. Can QE truly continue indefinitely or is there a limit?

See also: Base MHIT plan by Bank Negara Malaysia — a step in the right direction

Japan started QE back in 2001, meaning it has been at it for the past two decades, though its balance sheet really started expanding rapidly after the GFC. The Fed’s first QE was in 2009 whereas ECB launched its programme in 2015.

The surge in liquidity has not resulted in inflation, one of the main early concerns.

On the contrary, though it did fan inflation in financial assets, underpinning the yearslong stock and bond rally, which also widened inequality. Public debt in these countries is also rising quickly but QE has yet to result in any significant capital flight or currency devaluation.

But that threshold limit may turn out to be much lower in EMs. The reality is that there is a huge divide between what major developed economies and EMs can and cannot do.

The US dollar holds a privileged position as the global reserve currency and haven asset in times of crisis. Like it or not, the world has yet to find an adequate replacement. Foreign exchange (forex) is a relative measurement. Thus, there have also been limited fluctuations for the yen and euro, which are the other core currencies aside from the greenback, given that all three central banks are pursuing similar monetary policies.

The same cannot be said, however, for EMs. For now, the financial world is accepting of the QE undertaken in these countries as a necessary short-term emergency tool in the face of the huge exogenous shock.

For the majority of countries, QE was intended as a pre-emptive action — to prevent a liquidity crunch in the heat of the pandemic and to ensure their capital markets remain functional. For some, it was the most expeditious way to fund and push out large fiscal stimulus, given the urgency of the situation, without triggering a sharp hike in yields.

For more stories about where money flows, click here for Capital Section

But EMs should not be complacent of the risks. Just because there has been no visible adverse effect on their capital accounts and forex rates does not mean there will not be consequences in the future.

Indeed, S&P Global Ratings has already flagged the potential risks should QE extend beyond the near term, and particularly if these central banks are seen as monetising government debt. In a recent report, the rating agency raised the question of central bank credibility, their independence (from the government) and integrity.

Developed countries, on the other hand, are given great leeway on the basis of their transparent policy frameworks and fiscal discipline — though one could argue otherwise as evidenced in the case of the PIIGS (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain) nations during the European sovereign debt crisis.

That said, large-scale QE programmes used primarily to finance a rising fiscal deficit is a legitimate concern — and will quite likely trigger negative consequences down the road.

A case in point: There are some early anecdotal indications that foreign investors are getting antsy over the extent of Indonesia’s QE programme. Its central bank has been buying huge amounts of sovereign debt directly in the primary market, effectively funding the government’s fiscal spending — with suggestions that this burden-sharing cooperation could extend beyond the current year.

The rupiah has been the worst-performing currency against the US dollar in the region so far this year (see Chart 2). Bear in mind that Indonesia has a twin deficit and financing shortfall. Its fiscal deficit has widened well above its 3% cap, estimated at 6.2% this year, as a result of increased stimulus spending, raising some debt sustainability concerns.

The more reliant a country is on foreign capital, the more susceptible it is to capital flight, which would result in a combination of interest rate hikes, a sharp currency devaluation and surge in inflation that can devastate the economy. That was what happened during the Asian financial crisis (AFC) in 1997, in an extreme scenario.

Conversely, countries with high savings rates and robust domestic institutions will be more insulated from such foreign investor-driven vagaries. As such, we see minimal risks for Malaysia’s limited QE response to the pandemic. Bank Negara has a credible reputation and established track record for prudence.

The country has pared its reliance on foreign funding since the AFC — total foreign holding of debt securities amounts to less than RM209 billion, or about 16.3% of GDP. The Employees Provident Fund alone has some RM834 billion in assets under investment, of which 27.1% (roughly RM226 billion) was invested overseas, according to its 2018 annual report. In fact, we think there is room for Malaysia to expand QE, if necessary.

Nigeria is one of the few EMs to have been conducting QE for the last few years and thus may offer more guidance over the possible longer term effects. The Central Bank of Nigeria has been heavily financing government spending, following the price collapse of oil and gas, the country’s primary exports. The rise in its government securities purchases is positively correlated to the country’s weakening currency and double-digit inflation rates.

To be sure, no two countries are the same and the limits of QE for each is dependent on a host of factors, including political stability. But perception — often shaped by the Western media and institutions that also dominate the financial world — matters and, rightly or wrongly, EMs usually end up being seen in an unfavourable light. Same action, different perception — and quite likely very different consequences. Who says the world is fair?

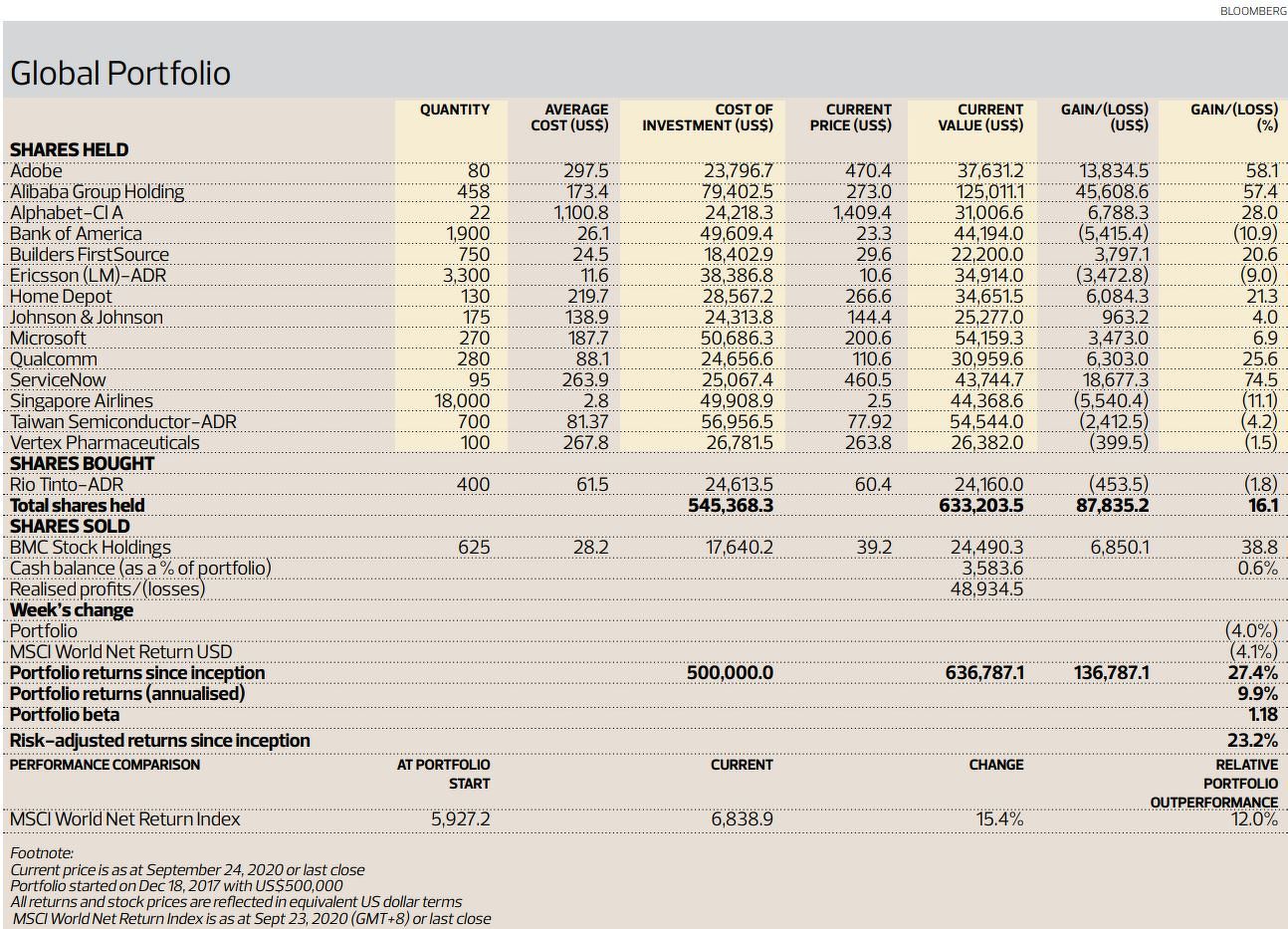

The Global Portfolio fell 4% for the week ended Sept 24, mirroring the broader market decline and paring total portfolio returns to 27.4% since inception. Nevertheless, this portfolio is outperforming the benchmark MSCI World Net Return index, which is up 15.4% over the same period.

All the stocks in the portfolio fell save for ServiceNow, which gained 1%. The top losers were Builders FirstSource (-10.8%), Bank of America (-9.1%), Alphabet (-6.8%) and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing (-6.3%).

We disposed of our entire holdings in BMC Stock Holdings, netting a 39% return. Proceeds from the sale were reinvested into Rio Tinto Group, the world’s second largest mining company. This decision is in line with our expectations that demand for iron ore and copper will grow on the back of massive infrastructure spending as part of government fiscal stimulus packages in response to the pandemic. Additionally, commodity prices tend to rise on US dollar weakness.

We disposed of our entire holdings in BMC Stock Holdings, netting a 39% return. Proceeds from the sale were reinvested into Rio Tinto Group, the world’s second largest mining company. This decision is in line with our expectations that demand for iron ore and copper will grow on the back of massive infrastructure spending as part of government fiscal stimulus packages in response to the pandemic. Additionally, commodity prices tend to rise on US dollar weakness.

Disclaimer: This is a personal portfolio for information purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation or solicitation or expression of views to influence readers to buy/sell stocks, including the particular stocks mentioned herein. It does not take into account an individual investor’s particular financial situation, investment objectives, investment horizon, risk profile and/or risk preference. Our shareholders, directors and employees may have positions in or may be materially interested in any of the stocks. We may also have or have had dealings with or may provide or have provided content services to the companies mentioned in the reports.