Democracy is an ideology (I had many years ago presented a paper titled “Freedom is a right, Democracy is an ideology” at a global forum). The premise of this ideology is that humanity’s progress is due largely to growing liberalism, of democratic practices and free-market capitalism. It relies on the assumption that individuals are able to make rational cognitive decisions for their self-interests. It accepts the story that voters know best. However, in reality, human decisions are based more on emotional reactions and humans largely think as a group — not as individual rational agents. (We will articulate this more comprehensively in our upcoming Special Report in Issue 1437, on a related topic.)

In the real world, there is a whole range of interpretations and degrees of democracy in practice. There is a presumption that representatives, elected by the people, will then govern based on the core principles and values mentioned above. But democratically elected governments and authoritarian leaderships are not mutually exclusive. We have seen it, past and present, in countries such as Hungary, Turkey, Argentina, Egypt, the Philippines, Indonesia and, to a certain extent, Singapore and Malaysia. Even the US, the champion of democracy and free and fair elections, is not above election manipulations, including gerrymandering and increasingly, voter suppression, and there is a whole discussion on minority suppression.

hat we are trying to say is that this delineation between democracy and autocracy is far from clear-cut and, indeed, the perception of what constitutes democracy can vary widely in different countries and sometimes, between how the world and its people sees a country. And while good for Western propaganda, it is not always useful in determining how successful a nation is, or the well-being of its people (see Box Article 1).

While it is true that many autocratic regimes have not done well economically, a democratic country, ruled by the majority, is not exempt from policy mistakes, mismanagement or theft either. A huge number of real-life cases immediately comes to mind. We have seen popularly elected governments make constitutional changes that erode civil liberties (including freedoms of speech, assembly and the press), undermine independence of the judicial system and weaken institutional check and balances — in order to suppress opposition and consolidate power. Oftentimes, unchecked power inevitably results in rampant corruption and in the worst-case scenario, economic disaster for the country and people. Case in point, Sri Lanka.

See also: When the majority votes with the minority’s wallet, capital walks

To be sure, there is no single all-encompassing measure of a nation’s success and well-being of the people. The matter is highly subjective. This article focuses on economic well-being and use of GDP per capita as the primary measurement. Generally speaking, the higher the income levels, the better off are the people. We are conscious and acknowledge there may be other measurements such as happiness, life satisfaction, health and environmental quality (air and water) and so on. Also, there will be people who would argue that economic well-being is not their goal. For instance, Bhutanese seek “happiness”. Yes, it is totally possible to be “poor and happy”. However, we doubt there are many who seek poverty as life’s goal. And for those who do, we apologise, but this article is not meant for you. And in all likelihood, you would not be a subscriber of The Edge.

There are many drivers for GDP growth. In this article, we pick three that we think are key to the economic success — or otherwise — of a nation.

The first is corruption and, more specifically, systemic corruption. The relationships between corruption, per capita income and economic growth have been the subject of many studies. Chart 1 shows the correlation between GDP per capita and the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) for select countries. (The CPI is a leading global indicator of public sector corruption undertaken by Transparency International. The scores range from 0 to 100, with 0 being the most corrupt and 100 being the least corrupt.) The strong positive relationship should not come as a surprise.

See also: Brains, beds and balance sheets: Where human capital becomes hard currency

One of the biggest impacts of systemic corruption on economic growth is by way of investments. Recall that we have previously discussed the critical importance of investments — both domestic and foreign direct investments (FDI) — as the main driving force behind the growth in productive capacity and productivity. Investment creates jobs and increases income levels for the people. Prevalent corruption, on the other hand, raises the cost of doing business and lowers the returns on investment, making them less attractive.

Corruption also results in leakages, wasteful and inefficient use of taxpayer monies and depletes the precious resources of the country. That, in turn, leads to poorer quality of infrastructure and limits the ability to provide better basic services such as education and healthcare, and aid benefits to the needy, to lift them up in life. It erodes trust in public services and government institutions — and usually entails cover-ups of wrong-doing and lack of accountability.

All of the above creates an environment that is not conducive for investor confidence. Foreign investors, in particular, are generally leery of investing in countries where corruption is entrenched, where there is low governance and a lack of transparency. Countries with poor infrastructure and lack of an educated, skilled workforce will find it especially hard to attract high-value investments. In short, the country and people are worse off.

The second factor is domestic savings, which also impact GDP through investments. Savings is the residual of disposable incomes after deducting expenses — and an important source of funding for investments. A high savings rate means a bigger pool of domestic money available to be invested. Conversely, low savings mean less money for investments, which translates to lower productivity and economic growth, fewer jobs and slower wage gains. When income cannot keep pace with inflation in cost of living, a higher proportion of disposable income goes to living expenses and even less gets saved. And that means even less for investments, feeding a vicious cycle. Chart 2 shows that there is also a positive correlation between domestic savings and income levels, albeit a weaker one (see Box Article 2 for a further explanation on this).

Countries with low and falling savings rate face huge challenges — as it must lead to lower investments and/or increasing reliance on foreign borrowings. For most emerging countries, foreign debts must often be denominated in US dollars, which raises foreign exchange risks. Plus, foreign investors (capital flows) have shown to be fickle and are a far less reliable source of funds. Very few countries in the world can keep borrowing without eventually suffering negative consequences. The US is the notable exception, by virtue of the US dollar being the global reserve currency.

For more stories about where money flows, click here for Capital Section

Last but not least, the third driver for economic growth is social mobility. Social mobility is defined as the change in one’s socioeconomic status relative to one’s current (and one’s parents’) position — upwards or downwards. It is often measured in terms of income, wealth, occupation and social class. The degree of upward social mobility reflects the equality of opportunity, to move up in your lifetime and/or to do better than your parents.

Low social mobility is most commonly associated with income-wealth inequality. In other words, your parents’ postcode plays an outsized role in your early childhood development and subsequent opportunities in life. Rich parents provide good housing, nourishment and healthcare for their kids, send them to the best schools and pay for extracurricular activities, give them exposure to vast experiences and open doors for future occupation through their extensive network of friends and associates. The opposite is true for children in poverty, who are likely to grow up with increased risks of chronic illness, less education, lack of physical security and confidence, and limited networking, all of which lead to poor employment prospects. From this start in life, the income-wealth gap usually will then continue to widen throughout one’s career. In short, it is far easier for a rich child to achieve higher and higher income-wealth and status in life and harder for a poor kid to escape poverty and move up the social ladder.

In addition to income-wealth inequality, upward mobility is affected by institutionalised discrimination (for instance, apartheid in South Africa) or non-institutionalised, social stratification such as India’s caste system. Affirmative action policies — aimed at increasing opportunities for select groups of the population in education, employment businesses and assets ownership — and other forms of widespread discriminations based on race or gender too have huge impact on social mobility.

We map the income levels and a measure of social mobility for select countries in Chart 3. There is a clear positive correlation between high social mobility and high per capita income. Why is social mobility so important in driving GDP growth, income levels and standards of living?

Low social mobility is sometimes described as “sticky ceilings” and “sticky floors”. Sticky ceilings (low downward mobility) create a sense of entitlement and rent-seeking class — and an environment that fosters nepotism and cronyism, which results in all the harmful fallouts including low productivity (not matching the most qualified persons to jobs) in the economy and opportunities for corruption (we have already explained the corrosive effects of endemic corruption on investments and growth above). Sticky ceilings greatly benefit a small group of elites at the expense of the masses, the rest of the population.

At the other extreme, sticky floors (low upward mobility) leave a pool of talent untapped and potentials under-developed — and worse, risk losing them altogether. The absence of economic opportunity, lack of upward mobility and prospects of prosperity through hard work generate pessimism among the discriminated. At best, it results in a large segment of apathetic workforce. At worst, it will accelerate brain drain. Both represent a loss of precious talent for the country as well as missed investments-economic opportunities. People do not invest in a future that they are pessimistic about and have low confidence in.

In short, equality of opportunity for all — based on the culture of meritocracy — promotes hope and optimism about the future (perhaps best encapsulated in the “American dream”, which is an integral part of the US’ economic success) while systemic discrimination is demotivating and leads to unhappiness and discontent.

More inclusive growth will improve productivity and reduce poverty. This means that instead of spending on welfare, money can then be directed to providing for, and improving access to, better quality housing, public transportation, education, community services and healthcare. Inclusive growth also promotes social cohesion and stability. These are all important considerations for investors.

Obviously, all of the three factors — corruption, domestic savings and social mobility — we highlighted above are very closely intertwined. If we had not already been abundantly clear, investment is the driving force for economic growth. Investments create jobs, improve productivity, develop and enhance talent pool and raise income levels, savings and living standards for the people. And more jobs translate to greater upward mobility prospects, a more motivated workforce, which in turn, attracts more investments, and faster economic growth. In other words, a virtuous cycle.

Hence, it is very important for public policies to focus on cultivating an environment that attracts investments — one that is absent of systemic corruption (with good governance and accountability), where there is equality of opportunity and prospects for upward social mobility based on meritocracy. Human capital — labour, skill, knowledge, experience and entrepreneurship — is, and always will be, the single most important factor of production in any economy. Policies aimed at more inclusive growth — higher social mobility — should include a combination of redistribution of wealth to reduce the income-wealth gap, enhanced social integration and protection against endemic discrimination. One country that ranks high in all three factors — absence of prevalent corruption, high savings rate and great social mobility — is Singapore, which, not coincidentally, also has one of the highest per capita incomes in the world.

The point we are making is that labelling a country as democratic or autocratic is less useful than looking into and describing countries with the drivers of economic well-being. It is time the world shifted to a new paradigm — one that is less driven by geopolitical intent.

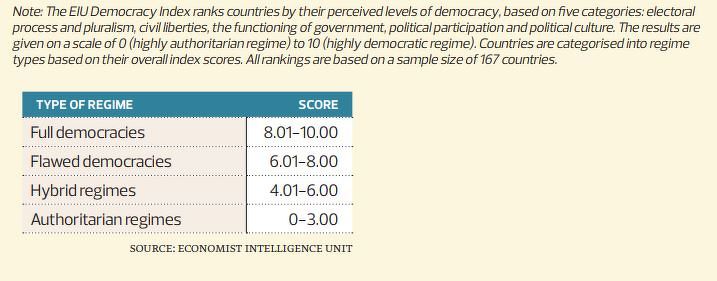

Box Article 1: Democracy is not always a useful measure of success or well-being

In the table above, we show a selection of countries ranked by (a) EIU Democracy index, which reflects their perceived levels of democracy (country with the greatest level of democracy is ranked 1); and (b) GDP per capita (PPP), to represent the economic well-being of the people (country with the highest income level is ranked 1). It is quite clear that greater democracy does not necessarily equate to higher income levels and vice versa. Case in point, India is ranked 48 (out of 167 countries) in the democracy index but only 107 in terms of per capita income. Conversely, China is ranked a lowly 155 in the democracy index but a relatively higher 65 in income levels. And Singapore is the second richest country in the world, after Luxembourg, even though it ranks only 68 in the democracy index.

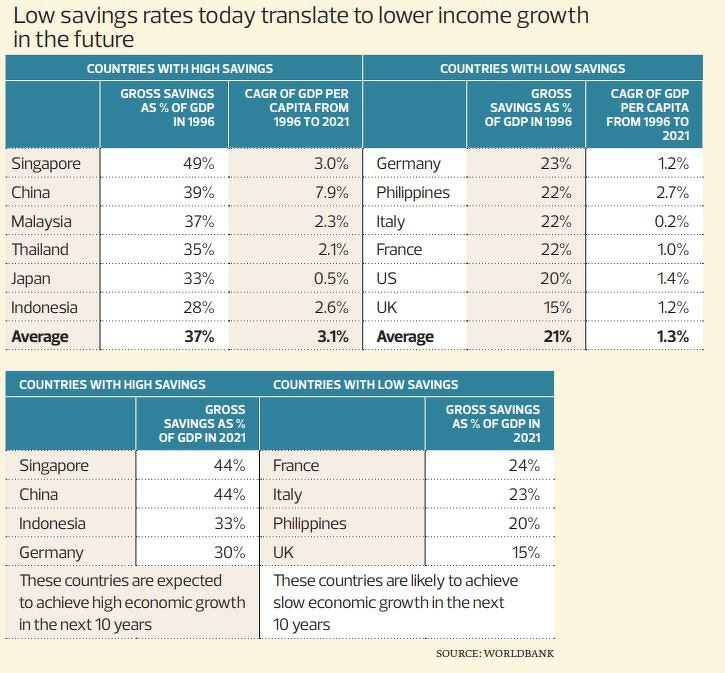

Box Article 2: Low savings rates today translate to lower income growth in the future

Statistics show that there is a positive correlation between domestic savings rate and income levels, but the relationship is not as strong (see Chart 2). Why? While domestic savings is one of the main sources of funds for investments, there are alternate means of financing. Countries with small savings pool can 1) tap foreign borrowings to finance domestic investments; and/ or 2) attract foreign direct investments (FDI) — but both alternatives have limitations over the longer term.

Additionally, Chart 2 is a snapshot at one moment in time. The impact of domestic savings on investments and subsequent income growth, on the other hand, plays out slowly over time, in years if not decades. Hence, to demonstrate its effects, we separate the sample countries in Chart 2 into two main groups — countries with high savings rate and countries with low savings rate in 1996. Historical statistics show that countries in the former grouping have, on average, higher income growth over the following 25 years (1996-2021). What does this tell us of the future?

We repeated the high-low savings rate groupings, this time using savings rate in 2021. Based on empirical evidence above, countries with low savings rate today will most likely see much weaker income growth over the longer term — unless significant structural reforms are undertaken to change the current course.

— End of Box Articles —

The Global Portfolio fell 3%, mirroring the MSCI World Net Return Index’s performance for the week ended Aug 24. There were only two gaining stocks in the portfolio last week — DBS Group Holdings (+1.1%) and Commercial Bank for Foreign Trade of Vietnam (+0.4%). Chinasoft International (-10%), Airbnb (-6%), and Guangzhou Automobile Group Co (-6%) were the biggest losers. Last week’s losses pared total portfolio returns since inception to 23.9%, trailing the benchmark’s 40.9% returns over the same period.

Disclaimer: This is a personal portfolio for information purposes only and does not constitute a recommendation or solicitation or expression of views to influence readers to buy/sell stocks, including the particular stocks mentioned herein. It does not take into account an individual investor’s particular financial situation, investment objectives, investment horizon, risk profile and/ or risk preference. Our shareholders, directors and employees may have positions in or may be materially interested in any of the stocks. We may also have or have had dealings with or may provide or have provided content services to the companies mentioned in the reports.