Living in a world where we are being tracked and analysed in real time by surveillance cameras sounds like a scene from Black Mirror or dystopian films. But this is already a reality in some parts of the world like London and China.

Besides Big Brother fears, it is also worrying that those cameras — powered by artificial intelligence (AI) — may propel unfair biases. After all, AI systems are trained using data, which can include biased human decisions or reflect historical or social inequities. It can also be a case where AI favours a certain group of people more just because that group of people were overrepresented in the training data.

With more organisations showing increased interest in AI, it is high time for us to address AI ethics. “Companies now use AI to help conduct talent screening, insurance claims processing, customer service, and a host of other important workflows. [We expect this trend to continue as our global survey finds that the] average spending on AI will likely more than double in the next three years. With heightened AI use will come heightened risk in areas ranging from data responsibility to inclusion and algorithmic accountability,” says Kalyan Madala, CTO and technical leader, technology group, IBM Asean.

AI should also be unbiased as it will be used in many critical sectors, including finance and healthcare. “The use of AI within these contexts raises significant legal questions, like those relating to agency and duties of care, and social questions, like the impact of AI on societal bonds and trust. [There is, therefore, the] need to have a coherent and sensible ethical framework underpin the development of policies and regulations governing the use of AI,” says Xide Low, senior associate, Clifford Chance Asia.

Asia Pacific’s take on ethical AI

Recognising that AI will be one of the building blocks of the digital economy, some governments in the Asia Pacific region — notably Singapore, Australia, and New Zealand — have issued principles, frameworks and recommendations to address ethical issues when deploying AI. Professor Simon Chesterman, senior director of AI governance, AI Singapore, shares that those guidelines tend to include variations of the following six themes:

- Human control — AI should augment rather than reduce human potential

- Transparency — AI should be capable of being understood

- Safety — AI should perform as intended and be resistant to hacking

- Accountability — Remedies should be available when harm results

- Non-discrimination — AI systems should be inclusive and “fair”, avoiding impermissible bias

- Privacy – The data that powers AI, in particular personal data, should be protected

“Singapore’s Model AI Governance Framework, for instance, focuses on AI being explainable, transparent, and fair as well as human-centric,” he adds.

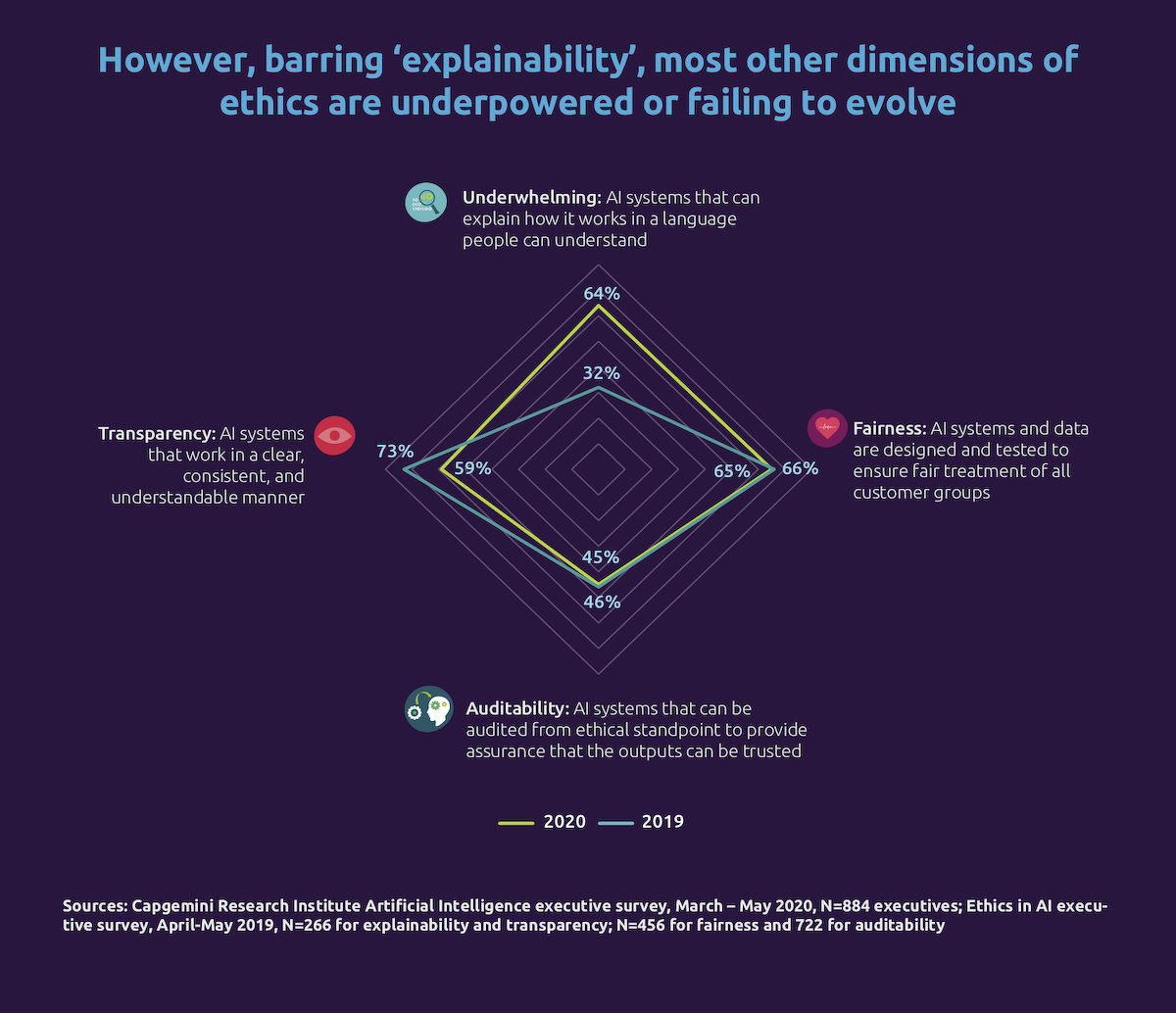

Despite the availability of those AI ethics frameworks, they are not yet widely adopted. Last year, Capgemini Research Institute found that only 54% of organisations globally had a leader responsible for trusted/ethical AI systems.

Zhao Jing Yuan, vice-president at Capgemini’s insights & data APAC, explains, “Most organisations are focusing on speed to market with AI applications and their short-term business impact on productivity and revenue. They neglect to invest in foundational ethical AI capabilities and technology tools.”

“Consequently, AI developers are unable to master and use the AI ethics framework in their daily work,” says Zhao, who holds a doctorate in statistics and applied probability.

Photo: Capgemini Research Institute

Operationalising AI ethics

Operationalising AI ethics requires ethics to be built into the frameworks of IT systems as well as the organisation. “This involves a cultural shift, evolving processes, boosting engagement with employees, customers and stakeholders, and equipping users with the tools and knowledge to use technology responsibly,” says Robert Newell, vice-president of solution engineering and specialist sales, Asean, Salesforce.

He adds that organisations can do so by:

- Cultivating an ethics-by-design mindset

To eliminate blind spots that can be ripe for bias, organisations should get a multitude of perspectives from different cultures, ethnicities, genders and areas of expertise when developing their products.

A “consequence scanning” framework, which helps teams envision unintended outcomes of a new feature and how to mitigate harm, not only benefits the end-product. It also encourages teams to think creatively about their product while still in the development phase; considering who will be impacted and how, as well as other potential problems. To empower them to better identify risks, organisations should offer training programmes that help employees put ethics at the core of their respective workflows.

- Applying best practice through transparency

No amount of testing in the lab will enable organisations to accurately predict how AI systems will perform in the real world. This is why accountability should be at the top of the mind throughout the product life cycle. Information should be actively shared with the right audiences to capture much-needed diversified perspectives.

Be it analysing data quality or gauging whether teams are effectively removing bias in training data, collaborating with external experts — such as academics, industry, and government leaders — will improve outcomes. Gaining feedback on how teams collect data can avoid unintended consequences of algorithms in the lab and even future real-world scenarios.

- Empowering customers to make ethical choices

AI ethics is not only limited to the development stage. Although developers provide AI platforms and may offer resources to help identify bias, AI users are ultimately responsible for their data. AI systems can still perpetuate harmful stereotypes if it is trained inadequately or using biased data. This calls for organisations to equip customers and users with the right tools to use AI technologies safely and responsibly, to know how to identify problems and address them.

In addition, IBM’s Madala advises organisations to create an effective AI ethics board and clearly define the company policies around AI. Walking the talk, IBM has an AI ethics board, which supports both technical and non-technical initiatives to operationalise its principles of trust and transparency. Aiming to guide policy approaches to AI in ways that promote responsibility, the principles outline IBM’s “commitment to using AI to augment human intelligence, to a data policy that protects clients’ information and the insights gleaned from customer data, and to focus on transparency and explainability to build a system of trust in AI.”

“[These efforts have] helped IBM create a culture of technology ethics that reaches its employees at every stage of AI development and deployment,” says Madala.

See also: Can AI be trusted?

Collective effort needed

“While AI holds exciting possibilities, public trust in technology is today at a low point. Increasing the level of trust in AI systems — by preventing bias, being explainable and reproducing results — is not just a moral imperative; it is good business sense. If clients, employees and stakeholders do not trust AI, our society cannot reap the benefits it can offer,” says Madala.

However, no organisation can solely address all the ethical concerns around AI. Capgemini’s Zhao therefore advises governments to work together with the private sector to identify AI ethical risk and issues, define AI ethics, and develop the building blocks of AI regulations.

“They should also facilitate multi-dimensional discussions among customers, business stakeholders, AI developers and researchers on AI best practices, development, deployment, AI interactions and the technology’s impact on the society,” she says. Such discussions can encourage everyone to develop and use AI responsibly while accelerating innovations.

Photo: Bloomberg