Now, as the global economy begins its arduous climb out of the black hole of Covid-19, the “investment biker”, as Rogers is also known, is no longer a lonely voice crying in the wilderness. No less than investment banking giant Goldman Sachs is now preaching the once-heretical gospel of the commodity supercycle. Repent, it proclaimed on Jan 5, a new commodity supercycle is at hand!

“Looking at the 2020s, we believe that similar structural forces to those which drove commodities in the 2000s could be at play,” argues the Wall Street investment bank in a November report entitled 2021 Commodities Outlook: REVing up a structural bull market. Similarly, Howie Lee, economist at Oversea-Chinese Banking Corp (OCBC), sees 2021 being the start of a major commodity price upswing that could last till 2022. Warren Patterson, head of commodities strategy at ING, says that commodity prices have seen their best start to the year since at least 2008.

There is no shortage of “signs and wonders” heralding this commodity bull run, which is not confined to just one type. Brent crude oil continued contract futures are up 37.08% year to March 8 at around US$70.67. A Reuters poll predicts palm oil prices averaging “nine-year highs” in 2021. Copper topped US$8,000 for the first time in seven years in December; Goldman Sachs sees copper reaching US$9,175 in 2022, testing the 2011 record of US$10,170. Even coal, with growing stigma as a dirty fuel amid wider embrace of sustainability practices, is now around 80.6% above its September 2020 low.

But doubters remain. “I’m a little bit sceptical about the idea of a supercycle re-emerging right now,” says David Jacks, JY Pillay professor of social sciences at Yale-NUS College, in an interview with BNN Bloomberg. While he notes that metals and mining will likely rally as a result of underinvestment over the past decade, he does not see soft commodities and energy catching fire similarly. “Grown commodities” like agriculture, for instance, typically fall in price over time while the opposite is true for “commodities in the earth” like metals.

See also: No silver lining in meltdown

Peaks and valleys

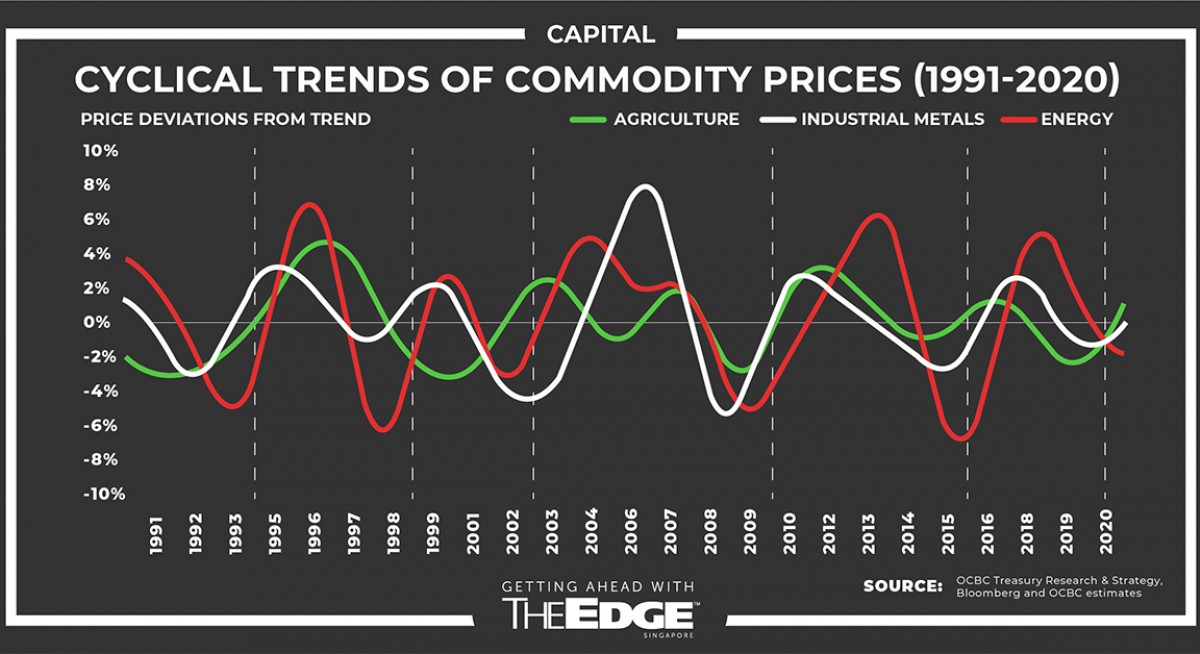

According to Lee, commodities tend to follow a notoriously cyclical pattern reflected in what economists call the Cobweb Theorem. As markets head towards price equilibrium, producers need more time to increase their supply of commodities by, say, drilling new oil rigs or increasing crop acreage. This temporary dislocation in supply and demand drives up commodity prices, creating a feedback loop where buyers stockpile inventories to avoid higher prices.

“Eventually, this results in overzealous producers supplying more than demand, driving down prices. This to-and-fro dynamic continues in a reduced magnitude until equilibrium is reached,” explains the OCBC economist. This ultimately gives rise to a market where prices fluctuate in cycles of higher and lower prices. Lee finds that agriculture, industrial metals and agriculture tend to swing in tandem in a cycle of peaks and troughs between five and seven years.

See also: US pitches mineral price floors, investments to tackle China

Gavin Thompson, vice-chairman of energy, Asia Pacific, at research consultancy Wood Mackenzie, thinks it may be a little early to call the current commodity bullishness a “supercycle”. Still, he is optimistic that commodity prices will be strong going forward owing to pent-up demand from consumers. The persistence of near-zero interest rates will cause a general uptick in prices across the board, with investors parking excess liquidity in commodities, on top of other investments they have already made.

Thus, Lee sees the cyclical rotation of funds potentially visiting commodities next, since these — unlike US equities and treasury bonds — have yet to test record highs. Investors could use commodities as an inflation hedge, with headwinds on commodities expected to be minimal even with vaccine roll-outs. With 10-year US Treasury breakeven yields currently above 2%, inflation expectations are rising in the markets, supported by resulting US Dollar weakness.

Yet the most important driver of recovery, says Patterson, will likely be China’s robust economic recovery. In 2002, China imported record volumes of crude oil, iron ore, copper and agricultural commodities, as its economy staged a strong second-half recovery from the pandemic. But it is doubtful if China will be able to sustain this frantic pace of economic activity in the long-term, as its economy could run the risk of overheating.

“That’s not saying that China cannot be a firestarter to a supercycle, but then you need some other economies to step in and be the real drivers behind that very strong demand growth on the commodities side,” says Patterson of ING.

He points to India as a viable candidate as the supercycle’s next torchbearer, if it can match the same pace of growth that China experienced in the previous supercycle after the GFC. Yet as the Indian economy is service-oriented rather than manufacturing-oriented, the country’s ability to drive a supercycle may be limited, says Jacks of Yale-NUS.

Black, green and gold

Still, the move to “build back better” could also be a strong alternative driver for a long-term commodity bull, should countries simultaneously work to transition to clean energy. The big winners from this, says Thompson, are likely to be so-called “transition metals” like copper and nickel, which are needed to build infrastructure like wind turbines and solar panels to harness sustainable energy. Prices for these metals have risen significantly over 2020.

“We are most bullish on copper in this commodity cycle. Not only is copper a proxy for bullish Chinese industrial activity, but the demand for electric vehicle adoption and electrical grid infrastructure would also be major supportive factors for the base metal,” says Lee. He sees copper breaking its record high of US$10,500/metric tonnes in the next twelve months on the back of a predicted supply shortage of approximately 200,000 metric tonnes in 2021.

Commodities are also attractive to investors as a good inflation hedge, since they do perform well under periods of high inflation. A classic inflation hedge, OCBC’s Lee sees gold likely testing record highs again next year. Robin Tsui, APAC gold strategist, State Street Global Advisors, also argues that gold actually does very well during economic booms, with demand driven by a rebound in the jewellery and technology sectors (See sidebar on Page 10).

An interesting metal to consider also is platinum, says Patterson, since it serves as a key catalyst in auto-manufacturing. As an economic recovery may spur a rise in demand for automobiles, platinum demand may also rise in tandem. The precious metal reached a six-year high on Feb 15, with recovery in Chinese jewellery demand and concerns about the vulnerability of South African supplies to Covid-19 driving the rally.

For energy, Lee does not see oil prices returning to US$100, though he reckons they will trend higher. High inventory levels, he says, suggests that energy prices could rise later than metals. Lee sees prices potentially rising, however, should new Saudi energy minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman make additional voluntary cuts to oil production in a bid to prop up prices. Patterson believes that oil prices could reach US$70/barrel by 4Q2022. Still, Bank of America sees global benchmark Brent hitting triple digits in the next few years.

The Biden administration is also seen to slow down shale growth, cutting global oil supply. Thompson of Wood Mackenzie also notes that a collapse in investment in new drilling has caused a permanent loss of 1.3 million barrels of oil per day, as firms looked to cut capital expenditure in the wake of collapsing oil prices. But this tightened supply could be balanced out should the Biden administration make an unlikely rapprochement with Tehran to revive the Iran Nuclear Deal, with global oil markets having to absorb new supplies of Iranian oil.

But James Trafford, portfolio manager and analyst at Fidelity International, thinks that recent moves by OPEC+ have pushed prices too high. “I don’t think a new supercycle is imminent in the oil market ... The current oil price level is really astonishing considering demand is still badly hit,” Trafford tells The Edge Singapore. He expects OPEC+ to bring back previously shuttered supply to bring oil prices back down into the US$50s by end of the year. Robert St Clair, strategist (SVP) at Fullerton Fund Manager, does not see Brent exceeding US$60–US$80 without a return of tourism and jet fuel demand.

Despite growing interest in “building back better”, Thompson does not see the growing switch to sustainable energy occurring quick enough to replace fossil fuels immediately. Wood Mackenzie’s Ed Crooks, vice-chair, Americas, sees oil only reaching its peak demand in 2039 and gradually declining thereafter. Nevertheless, Patterson of ING warns that more pollutive energy sources like coal will have limited upside as countries vow to achieve carbon neutrality. After all, coal is the most visible target for critics and activists trying to pressure everyone else into ditching the use of fossil fuel.

Within the broader commodities market, the dynamics of agricultural products markets will be somewhat different. OCBC’s Lee sees soft commodities having limited upside right now, though it will likely peak first within the coming year before base metals.

“The entire agriculture complex will likely continue to be supported by China’s needs for restocking, particularly in strategically important reserves like soybeans, as well as increased weather volatility,” he says. Inter-crop supply is expected to be tight despite growing interest in increasing acreage in 2021 due to the long lead time till harvest.

But as China looks to rebuild its herds of hogs after a nasty bout of African Swine Fever, palm oil prices could come under pressure. Greater demand for soybeans for hog feed creates soy oil as a by-product, reducing demand for palm oil — its closest competitor and oftentimes, a substitute. While this could see an 8.8% fall in purchases for 2020–2021, low supply in Malaysia has for now seen benchmark palm oil futures doubling from their May low to a near decade-high in January.

Analysts such as Avtar Sandu of Phillip Futures remain upbeat. “Despite day-to-day fluctuations in the palm oil market, crude palm oil prices are however expected to have their best annual showing in a decade as world economies emerge from the ravages of the coronavirus.

“Although price volatility has increased in the futures markets recently, fundamentals have not structurally changed. Further world usage of palm and other vegetable oils for energy is still staying at a very high level. This would require rationing the edible oil food sector. This will keep good prices relatively high unless biodiesel mandates are reduced,” he adds.

Playing commodities via SGX

There are many different ways investors here can take part in the potential upside of the new upcycle of commodities. For example, metalheads can also look into Fortress Minerals for individual iron plays. PhilipCapital analyst Vivian Ye sees the Malaysian-based rough diamond as a high-grade iron-ore play with significant exploration potential, with its Bukit Besi operation worth US$32 million with only 4.71% of the area explored. It also owns a 100% stake in Canadian-listed Monument Mining’s copper and iron project in Pahang. Fortress Minerals recorded a 477.9% patmi increase y-o-y in 3QFY2021 ending February, with sales volume growing 93.8% y-o-y owing to rising domestic steel demand.

For goldbugs, SGX offers the popular SPDR Gold Shares ETF for local investors looking to expand their exposure to gold. The fund seeks to reflect the performance of the price of gold bullion less trust operating expenses to give investors a hassle-free way of entering the gold market. It was the most-traded SGX ETF in 1H2020 as investors flocked to hedge their portfolios against Covid-19 uncertainty.

For energy plays, investors can consider China Aviation Oil (CAO), which Paul Yong and Jason Sum of DBS Research think is undervalued. They see it benefitting from a resurgence in domestic air travel in China — which has reached pre-Covid-19 levels as of October — with vaccinations being a further source of relief in 2H2021. With business brisk in the contango oil market, CAO is valued cheaply at less than three times FY2021 P/E excluding cash.

“In Asia, there is still a lot of value in Chinese energy equities, which have not yet moved to price-in the current oil price level. However, this brings added challenges given key players are state-owned enterprises with historically low profitability, rising upstream capex budgets, and geopolitical risk,” notes Trafford of Fidelity International.

Agriculture investors are familiar with planters Wilmar International and First Resources, with the latter sensitive to rising crude palm oil (CPO) prices. DBS’s Andy Sim and Alfie Yeo also recommend Japfa due to attractive valuations (five times FY2021 EV/ebitda) after it divested its 80% stake in Greenfields Dairy Singapore at 21 times EV/ebitda. Japfa’s dairy and swine operations in China and Vietnam should mitigate Covid-19 headwinds buffeting its Indonesia operations.