Panicked, she runs away to the forest hoping and praying for freedom, but she forgets the cardinal rule: “Never pray to the gods that answer after dark.”

As we learn from all fairy tales, wishes come at a price, and should your wish giver be of an evil nature, the price will be greater still. Addie unwittingly sells her soul to the darkness for a life, for freedom. But the cost is that she is forgotten, cursed to roam the earth without a soul who knows her and no one to remember her, as when she is out of sight, she is quickly forgotten. If she draws a line on paper, it melts away, and even her footsteps vanish as she walks. She grows to depend on the darkness, her only friend, and enemy. Adeline also never ages, and while she feels hunger and pain, she lives forever and the scars disappear as well.

However, everything changes in 2014 when she meets a boy, a particular boy. From the moment Henry utters, “I remember you”, Addie’s forgettable life becomes different.

V E Schwab’s new fantasy fiction novel explores memory, freedom and what it means to be human

Told in the third person, The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue jumps through 300 years of time, marking notable moments in the titular character’s momentous life. While the tale is a little slow at the start, it picks up and grips the reader through the centuries, folded in between her present with Henry and anniversary encounters with the darkness.

One of the many facets of the curse Addie faces is that she cannot tell anyone her real name nor can she say it, and the only time she hears it is when the darkness visits her. The significance of names in the story is rooted in identity and what it means to be an individual.

For instance, her nickname holds such deep meaning, “Addie was a gift from Estele, shorter, sharper, the switch-quick name for the girl who rode to markets, and strained to see over roofs, for the one who drew and dreamed of bigger stories, grander worlds, of lives filled with adventure.” Even the darkness — which fashions itself after a fantasy Addie often drew — is given the name Luc. The name is short for Lucien, but she notes that Lucifer may be more fitting. Names are powerful. Luc’s name is significant — it informs about the character, creating a memorable being, something Addie is robbed of.

An interesting question this book explores revolves around memory, and what it means to have lived. Addie often refers to her story or life being a palimpsest — a manuscript or piece of writing material on which later writing has been superimposed on effaced earlier writing — and how each encounter rewrites atop the other. She tries to create relationships but overnight, the memories fade, and while she remembers, they forget. “It’s like living with déjà vu. Only you know exactly where you’ve seen or heard or felt that thing before. You know every time, and place, and they sit stacked on top of each other like pages in a very long complicated book.”

Unable to be remembered or make a mark, Addie finds one loophole in Luc’s terms. “I can’t hold a pen. I can’t tell a story. I can’t wield a weapon, or make someone remember. But art,” she says with a quieter smile, “art is about ideas. And ideas are wilder than memories. They’re like weeds, always finding their way up”.

It is impressive how The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue weaves in artworks that vaguely resemble Addie (while the sketches and paintings could be mistaken for any woman, they sport her seven freckles). She inspires songs, and while the artists have no memory of how they formed the lyrics, these small victories are how Addie makes her unending life more palatable. That yearning to be remembered, a uniquely human condition that is painfully relatable.

While Schwab’s writing flowed seamlessly between poetic prose soaked in emotion and natural conversation, what struck me the most was how Addie’s character was constantly redefining what it means to be free. She admits to herself that in a way, Luc — no matter how malicious his intent — forced her to be free. She adds, “There is freedom, after all, in being forgotten.”

It is so telling when Addie realises that, “Freedom is a pair of trousers and a buttoned coat. A man’s tunic and tricorn hat”. It makes me wonder how radically different the story would have been if she had been a man, as her freedom would not once have been taken away, especially in the many ways she was being restricted as a woman. Addie constantly evolves and redefines freedoms despite her curse, and, in a way, she is grateful for it. “I suppose I prefer my freedom to my reputation,” she says.

The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue is, ironically, a memorable tale. One that — spoiler alert — has a satisfying end as she does not give in to Luc. Still, there is something poignant about Addie’s strength, especially as she is at the mercy of such an unyielding and selfish god/devil/darkness/ Luc (he has many names). She persists.

Henry describes belief in a way that I feel also sums up the book’s examination of memory and our human need to make a mark — “Belief is a bit like gravity. Enough people believe a thing, and it becomes as solid and real as the ground beneath your feet. But when you’re the only one holding on to an idea, a memory, a girl, it’s hard to keep it from floating away." — Lakshmi Sekhar

Choice, contrasts and change in the highlands

Choice, contrasts and change in the highlands

Choice, contrasts and change in the highlandsThe heart does things that the head may not fully fathom. Thus, Liew Suet Fun landed in Bario in July 2013 with several bags and 20 boxes. What made sense was that she loved her husband Peter Matu, her mountain man with a gentle soul, and he loved her, and they wanted to build a home in the interior highlands of Borneo.

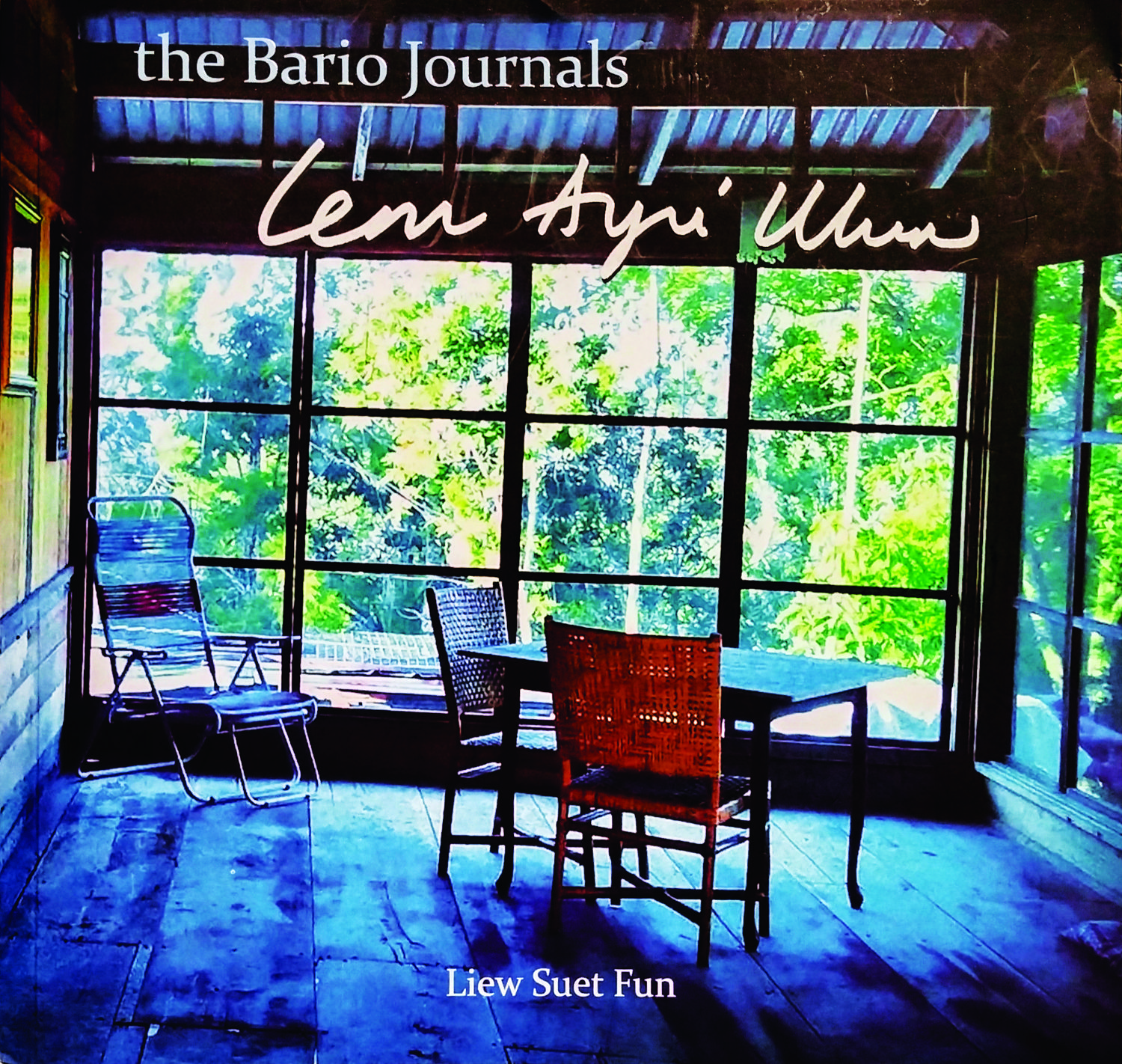

Liew, 52 then and a consultant turned writer, had thought it would be easy to adapt, having lived a decade in the US, UK and parts of Europe and Asia. It was not. You cannot find a society where there is more kindness and compassion, she says, yet a stranger has to struggle to forge reconciliation with Bario’s rice-planting Kelabits. But Lem Ayu’ Ulun (meaning this is life) and over the next 21⁄2 years, Liew becomes her choice, as she writes in her Bario journals, titled after that local phrase.

The book is introspective, intimate and poetic in parts. Liew wrote daily, sometimes twice a day, about the changes within herself and in the indigenous community around her, as she looked out of their timber house on the hillock, which Peter built piece by piece on land that was once a working farm for his father.

There is a sameness to her days — mists in early light, the warmth of morning sun, that first cup of coffee, laundry, cleaning, cooking, listening to lashing thunderstorms, dusk breezing in after a hot afternoon, dinner for two or sharing food in a longhouse — punctuated by trips to Miri, Kuching, Kuala Lumpur or her hometown Taiping for writing projects, to see the doctor, catch up with friends or settle some matters.

Trips into and out of Bario can be an adventure in itself, especially for visitors. Twice-daily flights departing from Miri take 45 minutes, winging passengers over dense carpets of green. Alternatively, there is the four-wheel drive along logging tracks from that same coastal city in north-eastern Sarawak, a journey of up to 13 hours.

Walking home in the dark, pushing motorcycle and tired feet along muddied paths, is routine for Peter and Liew. But surrounded by cloud-patched skies, rustic paddy fields and shadows clinging to mountainsides, gibbon song, bird cries, barking deer and hills receding into an unseen land, she began to see how tiny and inconsequential man is in the vast universe.

Lem Ayu’ Ulun, put together from Liew’s six journals, also tells how the Kelabits, once hunter-gatherers and headhunters, have held on to their traditions and habits even as they adapt to change. Australian missionaries brought Christianity to the hills after WWII, but it was the Bario Revival of 1973 that converted the majority of its people, for whom Sunday worship is now the highlight of their week. Electricity and water supply have not reached many parts of the interior but the young show an increasing fondness for sugary drinks, chips and instant noodles. Liew starts her book with a prelude titled Endings and chapter headings — Patience, Grace, Clarity, Eternity, Beginnings — lead readers in an arc that stops with her packing up to leave Bario in January 2015, for KL then Taiping, where different hills (Maxwell’s) beckon. Her reasons for leaving are not spelt out, but echoing wise words as old as the hills, “love deeply and let go freely”.

An impatient reader who wants more than personal reflections of Liew’s extraordinary experience in Bario and a peek at how the Kelabits — with their implacable endurance — live today may be disappointed. But Liew, an author of 18 books of non-fiction and poetry who has learnt to hold a hoe instead of a pen, says we have too many wants versus needs. Often, what is here and now is enough. — By Tan Gim Ean