But over the past 20 years, I’ve visited the island many times, often staying for weeks with my in-laws in the capital of Taipei. (My wife, Jean, grew up there.) Everywhere I’ve been in the country of 23 million people, I’ve found not only excellent food and eye-popping scenery, but a uniquely friendly population. There’s a chill amiability to interactions, even when I’ve struggled to make myself understood in Mandarin. Life is good, take your time, enjoy the small things — that’s the mood.

But over the past 20 years, I’ve visited the island many times, often staying for weeks with my in-laws in the capital of Taipei. (My wife, Jean, grew up there.) Everywhere I’ve been in the country of 23 million people, I’ve found not only excellent food and eye-popping scenery, but a uniquely friendly population. There’s a chill amiability to interactions, even when I’ve struggled to make myself understood in Mandarin. Life is good, take your time, enjoy the small things — that’s the mood.

And so it goes for me. When I arrive in the afternoon in Taitung, a four-hour train ride from Taipei, the summer sun blazes over the low buildings. Wohobike has lent me a nine-speed with wide gravel tyres, while my photographer, Brad, picks up a 27-speed FastRoad SLR 2 with lights, tools and panniers from a local Giant office. (The company’s islandwide network offers point-to-point rentals.)

Our rides secure, we coast into town to grab lunch at the Green House, a rickety restaurant known for its set meals — crispy mackerel, stir-fried bitter melon, thinly sliced pork belly topped with soy, nuggets of garlic and a thatch of shredded ginger. This is the kind of food I associate with Taiwan — flavourful but not flashy, delicious even when it’s not deluxe, above-average but unconcerned with being A-plus. It’s food I want to eat every single day. Afterwards, we wait out the heat with matcha slushies and mango waffles at Café Rebecca, a coffee shop located in a cypress-wood house that dates to 1947, when Taiwan was emerging from 50 years of Japanese colonial rule.

Every day, we figure, will go like this. Ride in the ever-so-slightly cooler mornings, break for a lunch that could last hours, and then, around 4pm, finish our rolling journey as the sun sinks behind the mountains.

When we finally set off, Pacific waves on our right crash into beaches strewn with tetrapods, the jacklike concrete structures that fight erosion. To our left, clouds snake through the steep green foothills of the Hai’an Range. Ahead, smooth, well-marked roads rise and curve with enough slope for a first day’s challenge. We ride through villages where surfboards are propped next to hostels and pause at a fruit vendor’s stall for fresh coconut juice. Sometimes we stop just to admire the dependably irregular vistas, where the sea meets the mountain meets the sky. Occasionally, I spot other cyclists, though I imagine in cooler months — November through March — there are many more. As we pass, we chant, “Jia you! Jia you!” — a Mandarin cheer that roughly means “Let’s go!”.

As the sun begins to set, we relish the cooler temperature, then start to worry. Shouldn’t we be at the Baonon Ocean Villa by now? We are tired and sweat-soaked. Text messages from the hotel’s manager blip on my phone: “Are you arriving soon?” Yes, but “soon” turns from 6.00 to 6.30 to 7.00. By 7.30, we are circling the pin on Google Maps. Why? Until — the entrance! A wooden door leads to a stately modern villa with a coffee station, stocked with pour-over devices and siphons, on the ground floor. Upstairs is a two-bedroom suite where the air conditioning is cranked to high.

The manager has left a note directing us to the village’s only restaurant, Sea of Clouds, which specialises in lobster. I choose a big one — our waitress, Li, warns us it’s pricey, at NT$1,000 a kilogramme ($45 for 2.2 pounds) — which the kitchen hacks into sixths and stir-fries with intensely flavoured scallions. There are also crispy chunks of fried fish, sticky-sweet spare ribs and morning glory stir-fried with garlic. We fetch tall bottles of Taiwan Beer from a cooler and fill little glasses. An elderly grandma toasts us and guzzles a glass of red wine. When I ask Li if the restaurant has any kaoliang, the high-proof sorghum liquor that is Taiwan’s national drink, she hands me a bottle to take home without charge.

And so it goes for me. When I arrive in the afternoon in Taitung, a four-hour train ride from Taipei, the summer sun blazes over the low buildings. Wohobike has lent me a nine-speed with wide gravel tyres, while my photographer, Brad, picks up a 27-speed FastRoad SLR 2 with lights, tools and panniers from a local Giant office. (The company’s islandwide network offers point-to-point rentals.)

Our rides secure, we coast into town to grab lunch at the Green House, a rickety restaurant known for its set meals — crispy mackerel, stir-fried bitter melon, thinly sliced pork belly topped with soy, nuggets of garlic and a thatch of shredded ginger. This is the kind of food I associate with Taiwan — flavourful but not flashy, delicious even when it’s not deluxe, above-average but unconcerned with being A-plus. It’s food I want to eat every single day. Afterwards, we wait out the heat with matcha slushies and mango waffles at Café Rebecca, a coffee shop located in a cypress-wood house that dates to 1947, when Taiwan was emerging from 50 years of Japanese colonial rule.

Every day, we figure, will go like this. Ride in the ever-so-slightly cooler mornings, break for a lunch that could last hours, and then, around 4pm, finish our rolling journey as the sun sinks behind the mountains.

When we finally set off, Pacific waves on our right crash into beaches strewn with tetrapods, the jacklike concrete structures that fight erosion. To our left, clouds snake through the steep green foothills of the Hai’an Range. Ahead, smooth, well-marked roads rise and curve with enough slope for a first day’s challenge. We ride through villages where surfboards are propped next to hostels and pause at a fruit vendor’s stall for fresh coconut juice. Sometimes we stop just to admire the dependably irregular vistas, where the sea meets the mountain meets the sky. Occasionally, I spot other cyclists, though I imagine in cooler months — November through March — there are many more. As we pass, we chant, “Jia you! Jia you!” — a Mandarin cheer that roughly means “Let’s go!”.

As the sun begins to set, we relish the cooler temperature, then start to worry. Shouldn’t we be at the Baonon Ocean Villa by now? We are tired and sweat-soaked. Text messages from the hotel’s manager blip on my phone: “Are you arriving soon?” Yes, but “soon” turns from 6.00 to 6.30 to 7.00. By 7.30, we are circling the pin on Google Maps. Why? Until — the entrance! A wooden door leads to a stately modern villa with a coffee station, stocked with pour-over devices and siphons, on the ground floor. Upstairs is a two-bedroom suite where the air conditioning is cranked to high.

The manager has left a note directing us to the village’s only restaurant, Sea of Clouds, which specialises in lobster. I choose a big one — our waitress, Li, warns us it’s pricey, at NT$1,000 a kilogramme ($45 for 2.2 pounds) — which the kitchen hacks into sixths and stir-fries with intensely flavoured scallions. There are also crispy chunks of fried fish, sticky-sweet spare ribs and morning glory stir-fried with garlic. We fetch tall bottles of Taiwan Beer from a cooler and fill little glasses. An elderly grandma toasts us and guzzles a glass of red wine. When I ask Li if the restaurant has any kaoliang, the high-proof sorghum liquor that is Taiwan’s national drink, she hands me a bottle to take home without charge.

The next three days follow a similar formula: Depart at 6.30am in the cooler morning air, ride 15 or 20 miles, then stop for a breakfast of scallion pancake with egg and Mr Brown canned iced coffee. Then, another couple of hours of riding. As we climb — 1,000ft, 2,000ft, 3,000ft — so does the temperature, until we can bear it no longer and take a break.

Once, we find a stand selling pineapple, sweet as candy and served with a mound of salt. Take-fives like this keep us going — keep us alive. Our bikes are sturdy and hold up fine, though Brad is always worried he’ll hit a bump and pop a tyre with all the gear in his panniers. I’m glad to have Woho’s bags, which keep the bike balanced.

We seek lunch where we can find it. On one lonely stretch of coast, there’s but a single cafe serving stewed ground pork on rice, sweet and savoury beef noodle soup and other Taiwanese classics. Another day, we descend into Yuli Township in the East Rift Valley, which separates the Hai’an Range from the more massive Chungyang Mountains. We discover, thanks to a train station clerk, that the township has its own signature noodles: yuli mian — yellow egg noodles in a clear broth, with thin slices of pork and, as always, loads of juicy scallions. Yuli mian aren’t that different from other Taiwanese noodle dishes, but they have an unadorned purity I admire. “We are noodles,” they seem to say. “Enjoy us as we are.”

By late afternoon on the second day, we find ourselves riding up to a recently built hotel. Just across the Red Leaf River, down small roads that twist through jackfruit and pomelo orchards, lies the stark and peaceful Silence Manor, 14 miles north of Yuli in Ruisui. Instantly, I fall in love with its soft, grassy lawn, its views of the mountains and especially its pools, a small one fed by a hot spring and a larger one where I float for an hour staring at the fish and insects cavorting at the surface of a nearby pond. For the first time in perhaps months, I truly relax.

Closer to Hualien, we stay at the Noosa Coast B&B, run by a young, cool Taiwanese couple who spent time in small-town Australia and rural India before opening this place a year ago. Perched above a sandy beach where cows traipse through in the morning, the Noosa is striking in the way its angular concrete lines frame the ocean in light and shadow. The loft suites have unique personalities: Mine is decorated with antique cameras, an old bicycle and a leather couch, like some bohemian Tokyo pied-à-terre.

Each of these lodgings is better than I’d hoped for — well-managed, beautiful, supercasual. And each morning, as we pedal away, I wish I could stay longer — eat more, relax more, explore more. In fact, I wish I could stop everywhere, learn everything. The east coast has a large aboriginal population — people who’d lived on Taiwan for more than 5,000 years before immigrants from mainland China began arriving in the 17th century. We see signs of their culture from the road — intricately carved wooden posts in Tafalong, and a girl embroidering colourful fabric next to the highway in Xinshe. These details underscore how little time I have to experience the region, even on a bike. The slower I go, the more it becomes clear that I have so much to see.

Some of the tourist landmarks along the route are entertainingly minor. On a bike bridge across the Xiuguluan River, we find a plaque explaining the plate tectonics that created the East Rift Valley. In one adorable village, we examine a 300-year-old well where tribal festivals were held. For maybe three minutes, we circle a monument that marks the Tropic of Cancer. The most memorable stop is at an aboriginal hunting school, where we fire bamboo arrows at targets and miss.

An unexpected ending

The next three days follow a similar formula: Depart at 6.30am in the cooler morning air, ride 15 or 20 miles, then stop for a breakfast of scallion pancake with egg and Mr Brown canned iced coffee. Then, another couple of hours of riding. As we climb — 1,000ft, 2,000ft, 3,000ft — so does the temperature, until we can bear it no longer and take a break.

Once, we find a stand selling pineapple, sweet as candy and served with a mound of salt. Take-fives like this keep us going — keep us alive. Our bikes are sturdy and hold up fine, though Brad is always worried he’ll hit a bump and pop a tyre with all the gear in his panniers. I’m glad to have Woho’s bags, which keep the bike balanced.

We seek lunch where we can find it. On one lonely stretch of coast, there’s but a single cafe serving stewed ground pork on rice, sweet and savoury beef noodle soup and other Taiwanese classics. Another day, we descend into Yuli Township in the East Rift Valley, which separates the Hai’an Range from the more massive Chungyang Mountains. We discover, thanks to a train station clerk, that the township has its own signature noodles: yuli mian — yellow egg noodles in a clear broth, with thin slices of pork and, as always, loads of juicy scallions. Yuli mian aren’t that different from other Taiwanese noodle dishes, but they have an unadorned purity I admire. “We are noodles,” they seem to say. “Enjoy us as we are.”

By late afternoon on the second day, we find ourselves riding up to a recently built hotel. Just across the Red Leaf River, down small roads that twist through jackfruit and pomelo orchards, lies the stark and peaceful Silence Manor, 14 miles north of Yuli in Ruisui. Instantly, I fall in love with its soft, grassy lawn, its views of the mountains and especially its pools, a small one fed by a hot spring and a larger one where I float for an hour staring at the fish and insects cavorting at the surface of a nearby pond. For the first time in perhaps months, I truly relax.

Closer to Hualien, we stay at the Noosa Coast B&B, run by a young, cool Taiwanese couple who spent time in small-town Australia and rural India before opening this place a year ago. Perched above a sandy beach where cows traipse through in the morning, the Noosa is striking in the way its angular concrete lines frame the ocean in light and shadow. The loft suites have unique personalities: Mine is decorated with antique cameras, an old bicycle and a leather couch, like some bohemian Tokyo pied-à-terre.

Each of these lodgings is better than I’d hoped for — well-managed, beautiful, supercasual. And each morning, as we pedal away, I wish I could stay longer — eat more, relax more, explore more. In fact, I wish I could stop everywhere, learn everything. The east coast has a large aboriginal population — people who’d lived on Taiwan for more than 5,000 years before immigrants from mainland China began arriving in the 17th century. We see signs of their culture from the road — intricately carved wooden posts in Tafalong, and a girl embroidering colourful fabric next to the highway in Xinshe. These details underscore how little time I have to experience the region, even on a bike. The slower I go, the more it becomes clear that I have so much to see.

Some of the tourist landmarks along the route are entertainingly minor. On a bike bridge across the Xiuguluan River, we find a plaque explaining the plate tectonics that created the East Rift Valley. In one adorable village, we examine a 300-year-old well where tribal festivals were held. For maybe three minutes, we circle a monument that marks the Tropic of Cancer. The most memorable stop is at an aboriginal hunting school, where we fire bamboo arrows at targets and miss.

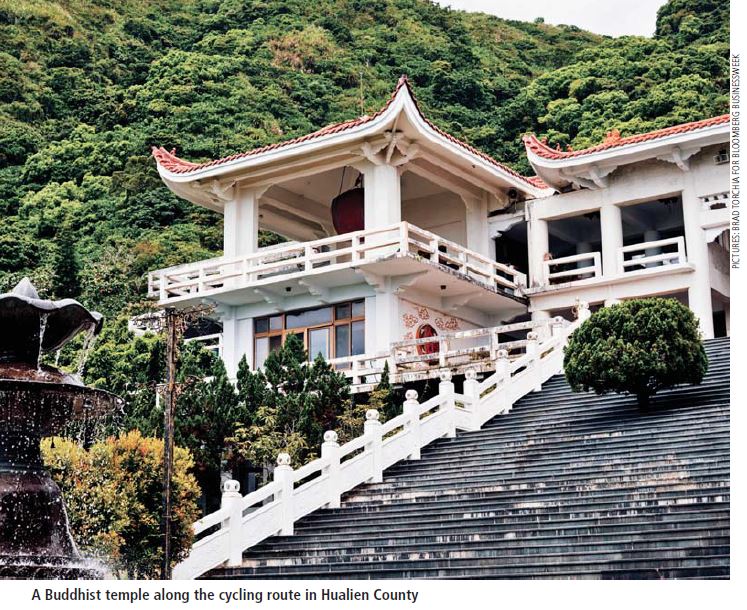

An unexpected endingAs we approach Hualien, a city of 100,000 that functions as the gateway to the east coast, I fixate on the Chihsing Tan Katsuo Museum, a former Japanese bonito flake factory that tells the history of the city’s fishing industry. It’s our final day riding, and Brad and I bike through a beachy neighbourhood with laid-back resorts, a bustling FamilyMart grocery and a small Buddhist temple behind a grandiose gate. We round the corner towards the museum, but before I see it, my nose twitches with the smell of a wet campfire. Uh-oh. Before us, where the museum should have been, is an utterly burned-out, empty lot. Nothing has survived the fire that, some guys at a nearby noodle stand tell us, consumed the building a week and a half before our arrival. I fall to the ground and begin to laugh. Why? Is there anything more ridiculous than to ride 150 miles to reach something that no longer exists? As I collect myself, I remember it’s almost lunchtime, and we’ll soon be eating at nearby Mu Ming, an incredible aboriginal restaurant that serves roast fish, grilled pork wrapped in lettuce and good, funky craft beer from local breweries. And soon after that, we’ll hop on the train back to Taipei, our muscles sore, our bellies full, our minds blazing with the struggles and successes of a delightful, delicious expedition. Those memories — whether a sweet pineapple or a simple downhill cruise — will outlast the lactic-acid build-up in my muscles. The taste of those mangoes, and the pork and shellfish and passion fruit, still lingers on my taste buds. Would they have tasted as good without the effort that went into getting there? One vivid memory provides a possible answer. Once, when we stopped to rest at an old farmhouse, the owner emerged to pour us cold drinking water from a natural spring, which he told us was from higher up the mountains. Atop one pass, we actually found the spring the farmer had described. The feeling of that icy mountain water on the back of my neck was worth every straining, sun-soaked “Why?” that led to it. Because I had earned it. — Bloomberg LP This article appeared in Issue 808 (Dec 4) of The Edge Singapore. Subscribe to The Edge at https://www.theedgesingapore.com/subscribe